Cars ten Kornberg Bak*

Department of Medicine and Health Science and Technology, Denmark

Received: 05/08/2015 Accepted: 15/09/2015 Published: 09/10/2015

Visit for more related articles at Research & Reviews: Journal of Social Sciences

The German Sociologist Ulrich Beck is best known for his book “Risk Society” which has been discussed extensively; however Beck’s claims about modern poverty have not received the same attention among poverty researchers. The individualization perspective views poverty as a relatively transient phenomenon and the democratization perspective views the risk of poverty as spread equally in the population. Both perspectives challenge the mainstream tradition of class analysis, and therefore both view poverty as largely independent of traditional stratification factors. In this article, I argue that Beck’s thesis about the individualization and democratization of poverty is based on narrow income based definitions and that (possible) empirical verification depends on the definitions of poverty and approaches used to examine poverty. My analyses show that the dynamic perspective (using income as measure of poverty) largely supports the democratization of poverty. My other analyses of relative poverty and social exclusion do not support Beck’s argument

Ulrich Beck, Democratization of poverty, Definitions.

Several internationally recognized sociologists [1,2] have declared ‘the death of class’, and Nesbit wrote a class obituary in the article ‘The Decline and Fall of Social Class’ as early as 1959. [3] explains the increasing inapplicability of the class concept by noting that traditional class divisions and interests are disintegrating as a result of the development of modern service economies However, [4] persist in a traditional class perspective with respect to social inequality and poverty. In ‘Cumulative disadvantage or Individualization?’ they test three theoretical perspectives: the class perspective, social exclusion and the theory of individualization. They conclude that the arguments for cumulative disadvantage and individualization are exaggerated and not empirically supported. Although various types of inequality are connected and cumulative, the researchers do not necessarily believe that this condition results in an identification of an excluded minority group that is suffering multiple deprivations. Factors embedded in life’s transitional periods awarded great importance in the individualization perspective, and although the researchers do not reject the factors as such, they aim to demonstrate that it is also important to include overall inequality categories, such as educational level, social class and occupational status, in our considerations. Only a few researchers have endeavored to test these theoretical perspectives using empirical research. These researchers applied different definitions of poverty and different types of data [5-10] Therefore; it comes as no surprise that the obtained results significantly differ. For example, and [7] applied comparative data that stem from the ECHP data and concluded that several of the theories related to poverty individualization and democratization must be rejected. However, German poverty researchers [5,8,11] inspired by the poverty theories advanced by Beck. These German research projects are characterized by their focus on income levels and periods of dependence on government benefits. Based on this focus, the studies conclude that most periods of poverty are short-lived and caused by biographical transitions in a person’s life due to health problems, divorce, etc.[8] rather than structural factors and, particularly, social class, which have occupied the center of attention in previous poverty research. This study aims to analyze and discuss the theoretical perspectives on poverty individualization and democratization. It focuses on one main question: what do the application of different definitions of poverty (income or relative poverty) imply in the testing of the theories of poverty individualization and democratization? The purpose is not to verify or falsify any particular theory. However, I would like to contribute to this discussion by demonstrating that the methodological questions applied in such tests are important to deter-mining the explanatory power of the theories in different empirical investigations and settings.

The theory of individualization presented in a German context based on research by [12-14] Beck’s primary claim is that individual behavior is now less connected to norms and values in a traditional sense and less dependent on collective identity in terms of social class[4,7].Largely, individuals are now forced to create their ‘own life’ and life biography. Leisering and Leibfried (1999) were strongly inspired by Beck’s theory of individualization when developing an alternative definition of poverty, presenting the core idea of their understanding of poverty in Beck’s terms. [8] divide Beck’s theory of individualization into three verifiable proposals that have been termed ‘democratization’, ‘demoralization’ and ‘biographisation’. In his theory of democratization, Beck claims that more individuals will be affected by poverty, which, however, does not imply that everyone is equally prone to poverty. Certain individuals remain more likely to be poor than others. In particular, Beck maintains that most individuals will experience poverty only as a temporary condition. Thus, poverty temporalisation refers to the various ways in which poverty may appear: as short, medium or long single periods or repeated periods within a person’s life [10]. This time dimension, i.e. the objective period of time and the subjective localization of poverty periods within a person’s life, is an important aspect of poverty analyses and has been neglected [8] Regarding the subjective impact of poverty on individual biographies, the notion of poverty biographisation is based on three basic assumptions: (1) Poverty is connected to specific life events and biographic episodes.(2) Objectively difficult circumstances are created by the biographical meaning ascribed to the circumstances by the individual and that being poor is perceived and evaluated in light of other life experiences.(3) The objective poverty period is overshadowed by a subjective time orientation that characterizes a person’s perception of poverty from a life perspective. The poverty individualization perspective is particularly characterized by the idea that poor people are a heterogeneous group (i.e. ‘the many faces of poverty’) and influenced by a range of causal relations that place only a small minority at risk of long-term poverty [7].

The empirical theory tests are based on data that stem from the three Danish Level of Living Surveys of 1976, 1986 and 2000 and related income register data on survey participants for the period 1991–1999, which were provided by the Danish Statistical Bureau. The surveys are based on interviews involving 5166 persons in 1976, 4561 persons in 1986 and 4981 persons in 2000. A total of 2335 persons participated in all three surveys [6] Thus, the strength of the data is the long-term span that is covered, and this makes it possible to test the theories of individualization and democratization. A clear shortcoming of the data is that they are over 10 years old. However, since the purpose primarily here is focused on methodological and measurement questions, the quality of data is much more important than the actuality of the data. Operational definitions of poverty I use two different operational definitions of poverty (50% median income poverty line and ‘relative poverty’) that have been used separately in two different studies [6,9,10] I use these different definitions to demonstrate the effect of a given definition on the testing results. In this study, I adopt a standard definition of relative poverty. That is, the poor are those individuals who as a result of economic or material causes have an enforced low standard of living that seriously restricts the possibilities for participation in normal activities and, therefore, restricts the options of individuals or households in relation to consumption, leisure time activities, etc., to a minimum, particularly when poverty has a long duration [10]. Although such a broad definition of relative poverty is commonly accepted by researchers as a fairly precise definition of poverty, most empirical research on poverty uses proxy measures of poverty, such as income thresholds [9].I test the democratization theory by applying a 50% median income as poverty line, based on related registration data for the period 1991–1999 [9]. I do not apply the 60% poverty line normally used within the European Union because this exact poverty line is not supported by scientific reasoning [15] Using the demographic method ‘Life Tables’ to analyze the probability of a person experiencing poverty at some point during adult life, I have analyzed the extent to which short-term and temporary experiences of poverty are evident within the Danish population. Despite heavy criticism of income as a poverty measurement [15,16], a criticism that I largely agree with (and which is reflected in our conceptual definition of relative poverty stated above), I use measurement of income because this measurement is the only possible means to compare the surveys from [6] and to study poverty that persists for a longer period of time. I tested the theory of temporalisation by performing register data analyses on poverty duration for the period 1991–1999 on an individual level. In this way, I have obtained an observation period that covers every year of the entire period in question, which enables me to study income mobility into and out of poverty.

Testing the theory of individualization and democratization

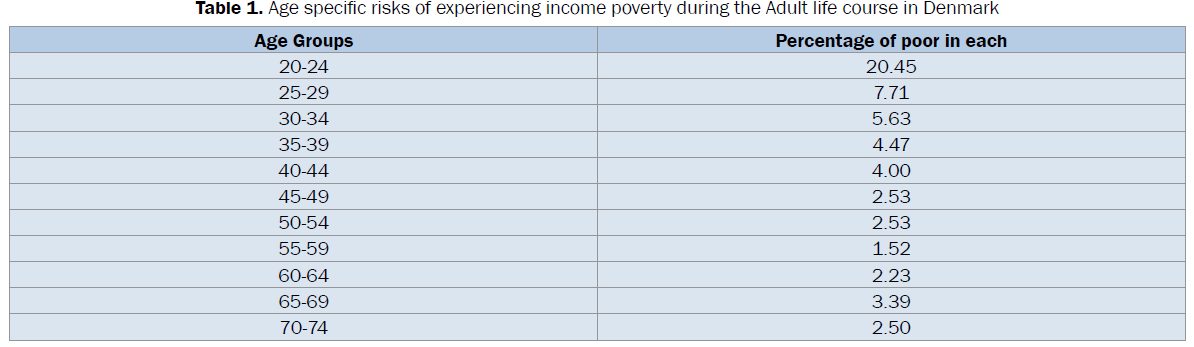

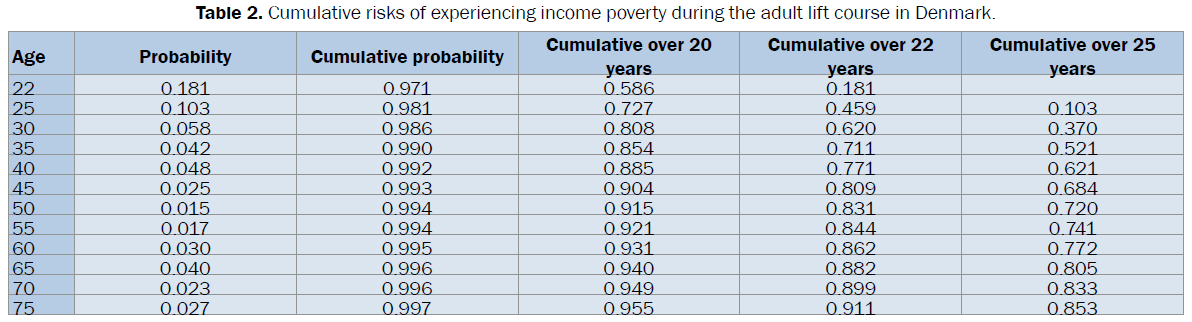

My empirical test of the theory of individualization aims to analyze the extent to which poverty has been ‘democratically’ spread within the Danish population, thus overstepping traditional social barriers of class, as maintained by [1,8] In light of the numerous studies on poverty prevalence and scope and when analyzed by means of longitudinal rather than cross-sectional methods, it seems increasingly certain that poverty is a much more common occurrence than generally assumed. However, the results largely depend on the poverty line applied [10] Therefore, an obvious means to ascertain the theory of democratization would be to analyze the extent to which short-term experiences of poverty are prevalent within the Danish population. We have performed this analysis based on calculations of age-related and cumulative risks of experiencing income poverty during adult life. The age-related probabilities listed in Table 1 show that whereas the probability of experiencing a period of income poverty is particularly high among the 20–24-year-olds (20.45%), the probability is much lower for individuals 35 years or older (below 5%). However, the cumulative probabilities listed in Table 2 show that the results are highly dependent on the age group applied as a starting point. From age 22 as a starting point, the results show that once the individual has passed his or her 75th birthday, the probability of that individual having experienced a period of income poverty is 91.1%. From a lifespan perspective, my results show that most individuals will have undergone at least one short period of income poverty at some pointing life. In addition, my analyses show no significant difference between males and females. However, my analyses also indicate that the probability of experiencing income poverty is at its highest among singles and singles with children. Young single mothers are particularly prone to income poverty; 91.4% of these mothers will have experienced a period of income poverty before reaching their 30th birthday. These results support the claim by [17] that even though periods of poverty usually do not last long, they affect most of the Danish population at some point, typically in early adulthood. Were we to rely only on these narrow income-based poverty measurements, we could relatively unequivocally support Beck’s theory of a democratic risk division with respect to short-term poverty experiences. However, do these income-based poverty studies paint a too gloomy picture of poverty in Denmark and do they actually provide sufficient proof that a process of poverty democratization has occurred? (Tables 1 and 2).

Testing the theory of temporization

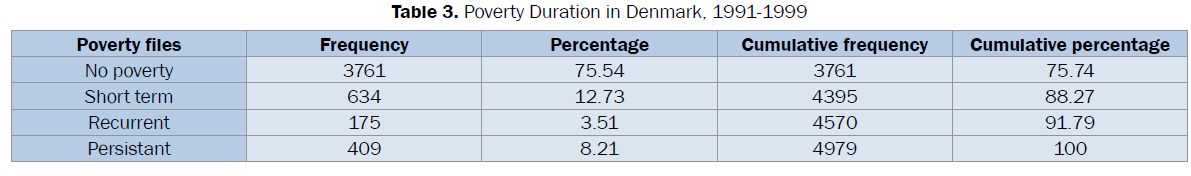

I test the theory of temporalisation based on registration data on income mobility during the period 1991–1999 to clarify poverty duration. The theory of temporization partly overlaps with the theory of individualization/democratization because both theories involve the claim that social class is now less important with respect to identifying poverty-prone individuals [4] In contrast to the surveys on long-term poverty formed by the European Commission, I apply a different, more precise definition that is derived from examining not only periods of continuous poverty but also including those groups of individuals who have been poor for more than 4 years within the 9-year period in question. Based on these data, we conclude that long-term periods of poverty occur more than twice as often in Denmark compared with the results obtained by various other European Union surveys [10] As shown in Table 3, approximately 76% did not experience poverty during the period 1991–1999. Approximately 13% experienced a period of poverty of no more than 2 years only once, and 3.5% experienced several periods of poverty lasting no more than 2 years per period. Accounting for 8%, the remaining group of individuals lived in long term poverty, defined as either at least one longer period of 3 years or several periods amounting to a total duration of poverty of more than 4 years [10] In particular, unemployed single mothers experience long-term poverty in Denmark (Table 3).

Overall, the results demonstrate that a traditional explanation that claims that we must retain a class-based perspective or that poverty has been individualized [1] must be rejected. Denmark deviates from the average level of permanent poverty and deprivation compared with most other European countries. However, the risk of being affected by poverty and deprivation is faced by the same groups of individuals as elsewhere. The risk of experiencing relative financial poverty and social exclusion primarily affects single parents, the unemployed and individuals who belong to the unskilled segment of the working class [7] However, classbased explanations and explanations of the individualization of poverty are less useful than the intersection between structural positions and individual biographies. Therefore, we emphasize the need for further empirical analyses that provide significantly more knowledge of the conditions that result in certain individuals becoming trapped in particularly vulnerable positions. Using ideas advanced by Beck, one could focus on those individuals who present potentially risky biographies within a collective risk group [1]. By focusing on the inter sectionalist of positions and conditions in which such risky biographies are involved, combining a class perspective with the perspective of individualization becomes significantly more persuasive [18].This persuasiveness is due to the individuals with risky biographies (the long-term poor and the socially excluded), who once lost control of their lives and are no longer able to recover, being recruited from these structurally determined risk groups. However, the point is that these individuals experience an individual rather than a shared fate with respect to the remainder of the collective risk group.

I thank Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com for the permission to publish parts of my article “Social exclusion or poverty individualisation? An empirical test of two recent and competing poverty theories”, in: European Journal of Social Work Volume 18, Issue 1, 2015: pp. 17-35. Carsten Kronborg Bak & Jørgen Elm Larsen. Published online 06 feb. 2014.