e-ISSN: 2320-7949 and p-ISSN: 2322-0090

e-ISSN: 2320-7949 and p-ISSN: 2322-0090

1Department of Public Health Dentistry, Sri Siddhartha Dental College and Hospital, Tumkur, Karnataka, India.

2Department of Public Health Dentistry, SRM Dental College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

3Department of Public Health Dentistry, Bangalore Institution of Dental Sciences Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Received: 01/11/2013 Revised: 12/11/2013 Accepted: 22/11/2013

Visit for more related articles at Research & Reviews: Journal of Dental Sciences

With the swelling number of immigrants around the world, there has been a growing concern about the gradual process of acculturation; Acculturation which leads health and oral health disparities. Now a days it is one of the major public health challenge which require development of measures that captures its positive and negative effects on individuals and community at large. This review has focused on its measurement and impacts on oral health.

Acculturation, Oral Health, Culture.

Any culturally diverse society is composed of numerous cultural group; indigenous people, recent immigrants, established immigrants and their descendents, all coexisting within a larger, predominant culture. This ethnic composition plays a key role changes in the public demand for services, and therefore in the provision of those services. Social justice requires the provision of resources and services on an equitable basis to all individuals and groups (Office of Multicultural Affairs-Australia, 1989). It is in this context that the concept of "acculturation" takes on a special social, political, economic and scientific importance [1].

Acculturation, as a term in anthropology, comprehends those phenomena when groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original culture patterns of either or both groups [2].

Acculturation is a complex phenomenon that can serve as a proxy for cultural norms and behaviors affecting care seeking, prevention behaviors, and ultimately,health outcomes [3-5] . Today acculturation has become one of the public health challenge. Reducing health disparities is a major goal for public and private health agencies.

There are four main domains of acculturation namely

• Assimilation (movement toward the ominant culture)

• Rejection (reaffirmation of the traditional culture)

• Integration (synthesis of the two cultures)

• Marginalization (alienation from both cultures) [1].

Assimilation

Is characterized by individuals who do not wish to maintain their cultural identity and seek a high level of interaction and participation in the dominant culture.

Separation

Is identified by the pattern of acculturation in which individuals retain and have a strong orientation toward their culture of origin while rejecting and avoiding interaction with the dominant culture.

Integration strategies

Is characterized by individuals who embrace and value both their culture of origin as well as the dominant culture.

Marginalization

Entails those individuals who are both excluded (either voluntarily or by force) from their culture of origin as well as from the dominant culture [6].

Acculturation, examined with regard to a wide variety of health behaviors, appeared to be beneficial to some health behaviors, and detrimental to others. Evidence collected in the United States has shown that acculturation exerts a positive effect on use of health services, negative effects on alcohol use and diet, and both positive effect and negative effect on physical exercise in different populations. The impact of acculturation on smoking was often modified by gender, with a lower likelihood of smoking in acculturated men and higher likelihood of smoking in acculturated women. Overall, acculturation to unhealthy lifestyles is an important explanation of the elevated risk of many chronic diseases, such as obesity, hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and cancer, among ethnic minorities in the United States [2].

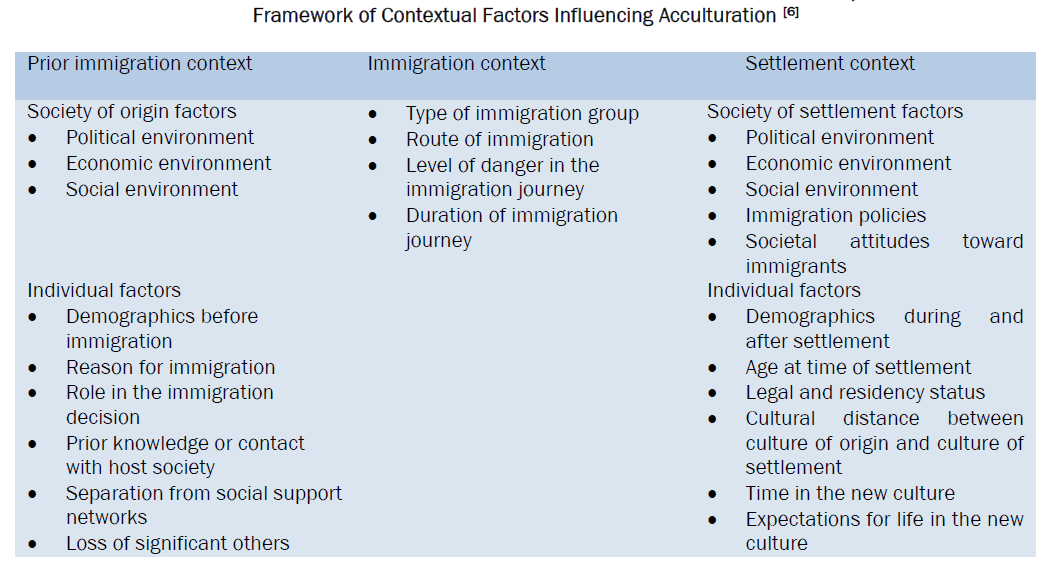

Measurement of acculturation[6]

Acculturation can be measured using

• Unidimensional:

Commonly used factors are language acquisition, language usage, frequency of participating in cultural practices, interpersonal relationships, cultural identity, family beliefs, and adherence to traditional values. e.g., Acculturation Rating Scale forMexican Americans; Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics

With unidirectional measurement we can assess single continuum, ranging from the immersion in one’s culture of origin to the immersion in the dominant or host culture.

• Bidimensional Models

Here the commonly used factors are ocial patterns and contextual factors.

Bidimensional measures maintenance of the culture of origin and adherence to the dominant or host culture). This framework identifies four distinct acculturation strategies (assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization) that are helpful in understanding how individuals adapt to a new culture. These four acculturation strategies are identified by where individuals fall within the two dimensions of the model [6].

Advantages to using shorter proxy measures include: simplicity of assessment, feasibility of collection in large health surveys, and limited respondent burden. Three proxy measures in particular have been shown to have high internal consistency and strong correlation between existing acculturation scales: language spoken (during interview or at home), proportion of life lived in the US, and generational status [7]. Language is considered the strongest single predictor of acculturation [8-10] while proportion of life lived in the US and generational status afford an assessment of the level of exposure to U.S. culture. Although often ignored, country of origin is also an important proxy measure that can provide important insight into the historical context, baseline cultural characteristics of respondents, and geographical context of exit. Therefore, when more thorough assessments of acculturation are unfeasible or unavailable, proxy measures that examine language usage, length of time in the US, generational status and country of origin are suitable substitutes [7,11].

Acculturation should be measured as a process rather than a state, prospective studies may further our understanding on the trajectory of immigrants’ oral health along the acculturation continuum. In addition, acculturation is bidirectional and reciprocal, rather than being limited to the minority groups. It is therefore relevant to profile the acculturation occurring in the mainstream (local) population of an ethnically diversified society and understand how such accuturation affects oral health. Qualitative researches may play an important role in understanding the acculturation phenomenon and its multifaceted implications on oral health [2].

Acculturation and Oral health

The impacts of acculturation on oral health receive attention only in recent years. The association of acculturation and oral diseases has been evaluated in many studies.

Recent study conducted in Bangalore city among tibetian immigrants [12] showed that 51.1% were affected by dental caries, mean DMFT 3.6%. 82.5% had gingivitis and 7.5% had periodontal involvement. 17.8% had dental fluorosis. 60% of Tibetan immigrants seek oral health care from dentist. Language barrier made it difficult to communicate the affected oral the health between dentist and patient in turn significantly associated with dental caries and periodontal status. Those who lived in Bangalore for 4 years or more and who can communicate in English appear to have better oral health and most likely to get dental checkup.

The association of acculturation and oral diseases has been evaluated in many studies. Study showed that adults who immigrated to the United States at an older age had higher prevalence of caries and periodontal diseases and higher treatment needs [13].

In Hispanic adults with orofacial pain, those who were English-speaking or with high nativity suffered less from the pain and its complications [14].

Canadian report showed that, the presence of calculus, gingivitis, caries and treatment needs among adolescent immigrants decreased with their length of residence (results from bivariate analysis) [15] . In the United Kingdom, Asian women who spoke English were less likely to have a child with caries [16].

In Australia, Vietnamese immigrants with medium level of acculturation had significantly lower oral health knowledge scores than those in the low and high acculturation categories [17]. It lends support to the ‘cultural marginality model’, which proposes that the partially acculturated individual, who is alienated from their traditional culture, but not yet integrated into the dominant culture, will be most susceptible to diseases [18]. While most public health programs target new arrivals, this research have underpinned the importance of tailored interventions for the partially acculturated immigrants

Utilization of dental services

Studies among other ethnic minorities in the United States demonstrated positive impacts of acculturation on utilization of dental care. The use of dental services increased with length of residence in the United States among Chinese elderly immigrants [19] and adults of Hispanic or Asian origins [20], but not among the Russian elderly [19].

Using a psychometric scale, authors reported that psychological acculturation facilitated dental visit of Vietnamese immigrants who were 35 years and above and who had spend 20% of their life in Australia [21].

That might be largely shaped by the culture of a community, such as the cultural norms and beliefs (e.g.fatalism), faith on other cures [22], and ethnic beliefs on disease causation and prevention [23].

The use of indigenous tobacco and areca products, which are proven carcinogenic, is common in some South Asian countries such as India and Bangladesh. This has led to a high oral cancer rate in these ethnic groups [24]. Observations on the immigrants’ use of these carcinogenic products and their oral cancer prevalence along the acculturation process will provide important reference for formulating timely and effective interventions.

Understanding and characterizing the process of cultural change is essential to the conduct of relevant oral health intervention. Basic services and health promotion activities should be made available to the immigrant population. Acculturation positively influences the oral health of these individuals by mediating their access to preventive and restorative oral health. Language is directly an important factor that should be considered during oral health education and treatment procedures. Preventive programmes should be organized at local community level in collaboration with key persons of the immigrant population.